Over the past decade, successive Lebanese governments have pledged to protect Lebanon’s oil and gas resources, expedite exploratory drilling and pass a raft of laws to strengthen the nascent sector.

The results have not been promising. Laws were passed late or not at all, while the launching of the country’s first offshore licensing round was delayed for nearly a decade.

Now, with the onset of Lebanon’s financial collapse, the government is looking to expedite a second licensing round. The goal in mind seems clear: to use a potential hydrocarbon find to pay back part of Lebanon’s massive $87 billion public debt and improve the country’s credit ratings, so that it can borrow at better rates.

The sustainable use of these potential resources for the future development of the country has been chronically absent from government policy.

As Lebanon begins exploring for oil and gas off the coast of Beirut, LOGI has looked back at over a decade-worth of oil and gas policy by successive governments. It is clear that long-term policy commitment have either seen long delays or have never been met, while short-term policies have been haphazardly added or dropped by successive governments without any clear reasoning.

The oil and gas saga began in 2008 with a ministerial statement of Fuad Siniora’s Cabinet that called for “activating” and “expediting” exploration, at a time when large gas discoveries had not yet been made in the eastern Mediterranean. The statement says Lebanon should prepare to launch the first licensing round with an aim to attract “prestigious and capable oil companies.”

Almost a decade later, Lebanon is just beginning to explore, while other eastern Mediterranean nations already extracted hydrocarbons from large discoveries. Why? Between 2013 and 2017, two crucial decrees were not ratified by the government.

LOGI at the time recommended that Parliament undertake its role in establishing a formal investigation into the matter, in order to ascertain why this delay took place. Till today, we have no answer.

In 2009, a new Cabinet was formed under Saad Hariri, and limited itself to “create an oil law.” This was achieved the following year with parliament’s adoption of the Petroleum Resources Law.

But delays soon began. In 2011, the Cabinet of Najib Mikati began referring to potential Lebanese hydrocarbon resources through the lens of Israel’s attempts to take over the country’s land and water.

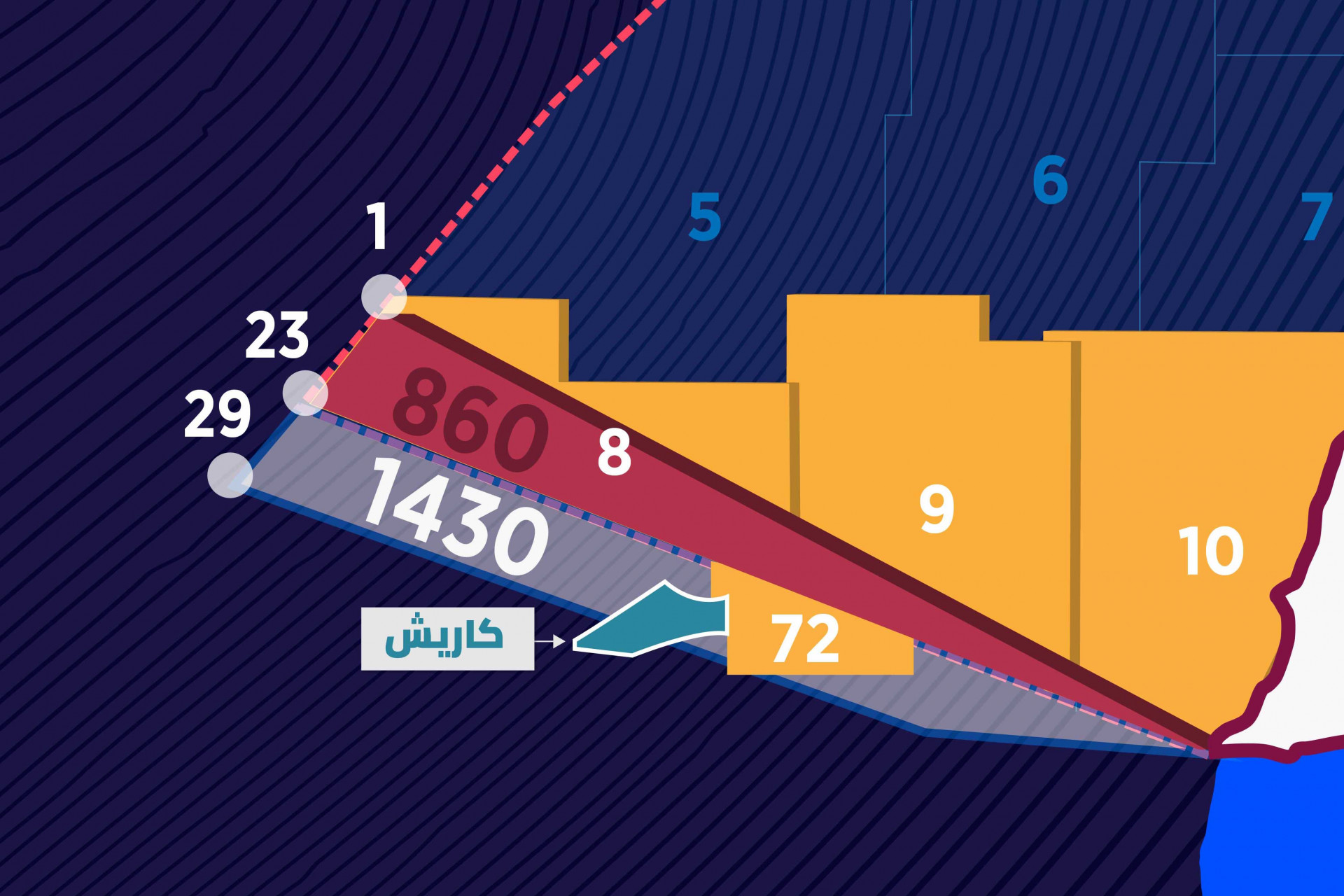

The Cabinet’s policy statement calls for delimiting Lebanon's southern border and adopting a “unified strategy,” to defend Lebanon from Israeli encroachment and solve the maritime border dispute.

Till this day, there is no such strategy and three successive US.-led attempts to mediate a solution to the maritime dispute have failed.

The 2011 statement also sets a high-ceiling: transforming Lebanon from a hydrocarbon importer to a producing nation after 2011.

Mikati’s Cabinet also said it would launch the first offshore exploration round, complete procedures to be able to undertake onshore exploration and delimit the maritime border.

The government lasted three years, but Lebanon was scarcely closer to achieving those goals by the end of it. Therefore, when Tamam Salam formed a government in 2014, the ministerial statement again called for the same: expedite the first licensing round, affirm Lebanon’s right to its oil and gas and accelerate efforts to delimit the border and exclusive economic zone.

Again the government failed to proceed with the first licensing round, and little changed on the other fronts. Hariri’s second government in 2016 all-but copied and pasted the same language from the previous two statements: Lebanon’s affirms its right to its oil and gas wealth and will seek to demarcate its borders, and will expedite the first licensing round and issue relevant decrees. It was during this government that the two much-delayed decrees for offshore exploration were endorsed.

In 2019, Hariri’s third government called for expediting the second licensing round and again called for preserving Lebanon’s right to natural resources and delimiting the southern border.

It also said it would endorse a draft law for onshore exploration and another to create a sovereign wealth fund, as well as issue implementation decrees for the law on Strengthening Transparency in the Oil and Gas Sector, a law LOGI lobbied for.

None of these goals, save launching the second licensing round, were met.

This leads us to the statement of the current government of Hassan Diab, which once again urges action against Israeli attempts to steal Lebanon’s oil and gas wealth and a resolution to the southern maritime border dispute.

The statement for the first time calls for strengthening Lebanon’s air force and navy to protect its exclusive economic zone and local waters.

It also calls for adopting a law to create a sovereign wealth fund while it drops, without justification, the previous Cabinet’s push to endorse an onshore law.

Diab’s policy statement also calls for renewing the mandate of the Lebanese Petroleum Administration, or appointing a new one. The LPA has been functioning in a caretaker capacity within an uncertain legal framework for over a year now after their mandate expired in December 2018.

And after over a decade of delays, the policy statement cites, perhaps aptly, that the oil and gas sector is the ”sector of the future.”

Read the full "Lebanon Oil and Gas Newsletter" for February 2020, published by Kulluna Irada and The Lebanese Oil and Gas Initiative (LOGI) here.